The Australian Institute of Architects this May held its annual conference on the theme The Changing Role of Risk in Architecture. A fantastic group of international speakers prodded and poked the idea of risk from all angles, but mainly from a higher plane than we typically think about it: “How to stay away from claims”.

On the contrary, virtually every speaker advocated boldly tackling the Tiger of Risk, and advancing stature and reputation by doing so.

Kasper Jensen (3XN, Denmark & Sweden; 3xn.com) noted “The entire profession is at risk if we don’t evolve constantly.” Jeremy Till (Head, Central St. Martins, UK; jeremytill.net) asked “Do we remain hopeful? We have to … else we allow Risk to dominate us.”

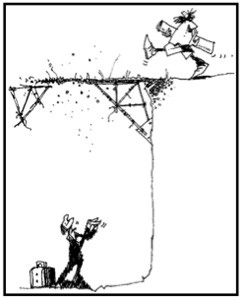

Manfred Grohmann (Bollinger + Grohmann Engineers, Germany) the one engineer on the podium observed: “Risk? I do not know the word. I know what I am doing”. He commented on his Architect clients: “They are always trying to drag us over the edge. We follow them to the edge, then we stop.”

His thought begs the question: Do we know what we are doing? I think, all too often, we don’t. We make assumptions, rather than finding out, and in that create about half of our own risk problems.

Why do we avoid the risk discussion?

I think that we avoid engagement on issues of risk because it has a negative connotation, and we designers want to stay in positive territory (make that “safe” positive territory). Consequently, we miss the diverse opportunities that many risk situations provide.

Back to the idea of making assumptions: Virtually every project (or every project we’d be interested in) is missing a lot of key information at the outset. The design process itself unpeels the onion, and slowly reveals the real detail of the design brief. The very act of design is one of choosing solutions – at both the macro and micro level – from thousands or millions of options. Much of this choosing takes place somewhere in the back of the brain, and often involves processes that are more intuitive than logic-based.

In this framework, we become exceedingly used to the idea of making assumptions whenever the way forward is less than crystal-clear. And in this mental framework, we all too easily make assumptions without thinking through the potential risk consequences of those assumptions. And – VOILÀ! We get into trouble.

We ignore the signs, don’t buckle the seatbelt or put on the safety vest, and march headlong into danger.

“Solicitors for clients have been crafting these deep pits covered with leafy branches along the architect’s path for years.”

So? What’s the answer?

In this mental framework, how can we ensure that our designers stay away from danger, but at the same time, think positively about risky situations and design ways to work with and around them?

One way is to use tools that help us tune into and manage risk. In an upcoming post I will talk about some of the useful, available tools.

Strategic vs. Tactical risk thinking

Another way is raise the awareness of risk with your team, and to separate Strategic risk thinking from Tactical risk thinking. In Strategic risk thinking, we focus on why we want to take on a project and cope with the risks it entails. That thinking goes well beyond financial reasons: Why would the project be important to our bigger business picture?

Strategic risk thinking also means thinking creatively about the risks involved: Are there alternative ways of approaching the project and the client that add value for the client; that can be traded to re-distribute the risk load? And a lot more – this one topic could be a small book all by itself.

Tactical risk thinking is different: it looks at the risks in the package (including multiple approaches based on the Strategic analysis). It asks detail questions: How can we mitigate each of the risk issues found? Do we need a project manager with different experience, or different social skills? Do we need specialized training? Do we need to negotiate key contract provisions? There are a lot of questions at this level that require answers, if (to use Grohmann’s criteria) we are to “know what we are doing”.

Risk Value Proposition

Having done both of these levels of risk thinking, you are now in a position to put the conclusions together, into a “Risk Value Proposition” that is in the first instance client-focused, and in the second, firm-focused. Then, sell it to the client. If it is creative, original, logical, and fair – and if the client is the sort of person or organization you’d want as a client – there is a pretty good chance of coming to a meeting of minds.

——————————————————————–

This paper has been submitted for inclusion in the PSMJ Project Management newsletter – for more info see: http://www.psmj.com/publications/newsletters/index.cfm

Posted by