Design Process Anatomy

This is Step 7 on the pathway to Taking Control.

Design process is a complex beast, resistive of analysis. It is complex for the 7 reasons listed in Present Reality Explored (Rapidly evolving environment, Information overload, Fragmentation of responsibilities, No framework for coordination & integration, Downward pressure on fees, Difficulty in maintain quality, and Increasing liability & risk).

It is resistive of analysis for several reasons (see side bar).

Many years of studying scores of design firms across 3 continents convinces me that there are three high-level components to design: Inputs, Process, and Outputs. Inputs are unique for every project (some more unique than others). Accordingly, outputs will also be unique if the process is responsive to the inputs.

Design process, on the other hand, is universal, regardless of the inputs and outputs. That doesn’t mean that every project has identical processes – far from it. It does mean, however, that the process set employed to tackle a particular project is selectively drawn from a universal set of processes, consciously or unconsciously.

Mapping design process

These processes can be mapped (see sidebar).

“Coding” of the process may seem superfluous – something nobody needs to set up in order to design a project.

However, it becomes very important the moment you try to create a database structure for the management of design, where links are required between a large range of design management functions.

This allows a database to link all manner of project data, across many projects, and still be able to drill down to exactly the Stage > Task > Action sequence on any project in the database. I call this “DDNA” – Design DNA – a simple corollary of the far more complex DNA of any living thing. How this structure works is shown in the iProjects software, discussed … (article & link to come).

Helicopter view vs. Microscope view

Uncoiling the DNA of design process is useful and necessary in order to design software to manage design processes, but it doesn’t present the “big picture” of how the design process operates. For that, we need to stand back and look at the complex interactions that occur on virtually all design exercises.

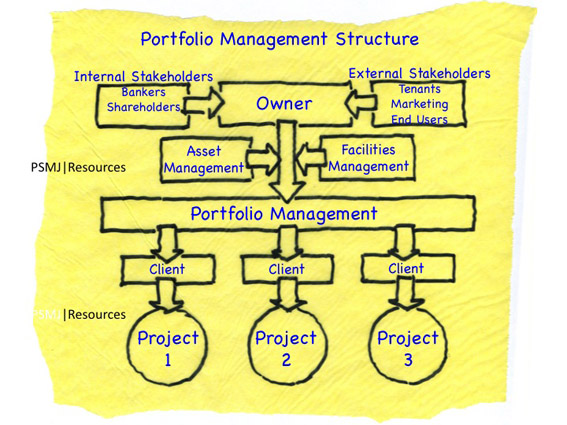

This “big picture” can best be understood by thinking about design inputs as a complex set of forces that impact on the design. At the highest level, we see all the stakeholders: clients, owners, their agents, users, and the design team. In the model below, we see the overall structure for a “portfolio” of projects – termed “Program Management” in PMI (Project Management Institute) lingo.

In this model, the “Client” is the entity that the design firm deals with – which might be the same across several projects in a portfolio, or different.

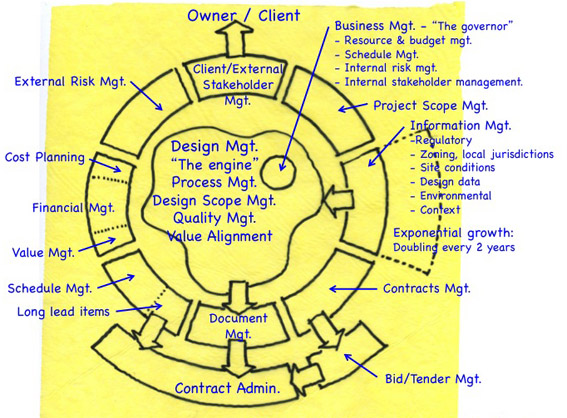

Each one of these projects, in turn, has its own complex set of external and internal functions, shown in the diagram below.

The outer ring of 8 segments comprise the Project Management function, with some related sub-management roles.

Design Management

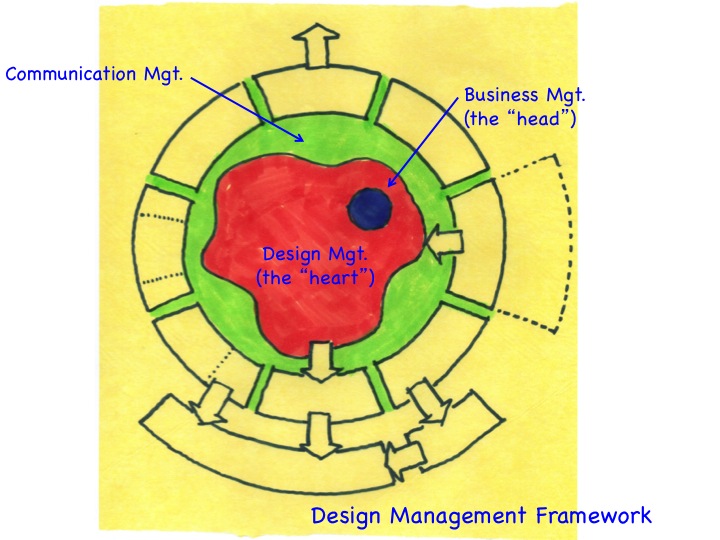

Inside the ring of Project Management is the Design function. For each design firm, there are two main components: Design Management and Business Management.

Note the Mitsui Fudosan example from Japan – see sidebar.

If we look at the space inside the Project Management ring, we find the Design function, comprised of Design Management and Business Management of the design firm, surrounded by a fluid “glue” that connects these processes to the Project Management functions around them.

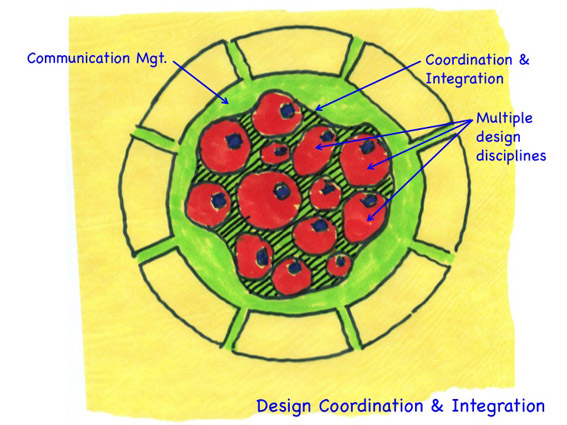

This is a fairly simple, amoeba-like structure if there is only one design consultant. However, for most projects, there are multiple design entities that comprise the whole design team. There are often a dozen or more of these “blobs” of design functions – in this case, 13.

The shaded area represents the essential coordination and integration functions necessary to successfully complete the project.

This diagram is not all that complex, but consider that within each one of these cells, there are hundreds of unique actions going on, different for each design discipline, and different for every unique project, each requiring some level of coordination and integration across the rest of the amoebic system.

In living creatures, enzymes perform this function. In architecture, nobody does – at least not very well. Great outcomes are more an accident of coincidence than a predictable result.

Here, precisely, in the interstices between the cells in the amoebic-like structure of design, is the essence of the problem facing 21st C. architects: Who is responsible for the project-wide management of coordination & integration function at the molecular level?

Most assuredly, it is not your average Project Manager. In my experience, most of them wouldn’t have a clue as to how to orchestrate the interplay of inputs, processes and outputs of multiple cells in the delicate dance of design.

This role is a unique discipline, that doesn’t yet exist, requiring:

- Extensive experience directly in one or more of the disciplines being coordinated,

- An overall awareness of how all of the components fit together to create a comprehensive design result, grounded in time, money & quality, and

- The ability to work effectively across all disciplines, to understand their issues and constraints, and to guide the synthesizing of their outputs.

This Design Management role is deeply intertwined with both Quality and Risk Management, and critical to successful Client Relationship Management. The coordination and Integration function is core to the ability to provide certainty to the client, and thus to the success or failure of the whole project.

But it is much more complex than that. In my view, architects cannot become masters of their own destiny unless the profession (almost surely requiring the participation of schools of architecture) figures out how to effectively manage this molecular-level coordination and integration. However, doing that alone won’t unwind the trend toward erosion of relevance.